‘Why were we messing around with trigonometry? We should’ve been learning about taxes!’

My oldest friend often airs this complaint about our school days, usually down a couple of pints. Perhaps he’s right, though I doubt it would’ve helped. (I did learn trigonometry, after all, and the only tangents I can calculate are ones like this.) Plus, taxes are like death: something to accept, not understand — much less cheat. No: what they should’ve taught us is how to wait.

It’s not that there weren’t enough opportunities to learn it. Childhood, as I recall it, was an exercise in waiting. Waiting for holidays and birthdays, festivals and friends, for the rain to stop, the bell to ring, the Sunday cartoons to start showing. Most of all, it felt like an interminable wait for childhood itself to end, for real life to begin. With all of that training, one would think we’d be experts at this game, masters of the art of patience.

And yet.

I could bet — if I had a penny not already owed to some billionaire — that even as you read this, you’re waiting for something. An email, a phone call, a report from a doctor, a letter from the government, a sign from God. And chances are that it’s a small fire burning at the back of your mind, driving you to fidget, to doomscroll, to stand in an alley sucking on a vape. (I’m not projecting; you’re projecting.)

It doesn’t help that our culture seems to treat waiting as some kind of personal failure, a punishment for chumps. Podcasts dangle early access to episodes. Shopping sites nudge you to ‘get it today,’ Even my bank keeps offering me savings accounts with ‘instant access’, presumably designed for instants where I have a gun to my head.

It feels futile to complain about this glorification of impatience, let alone fight it. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t.

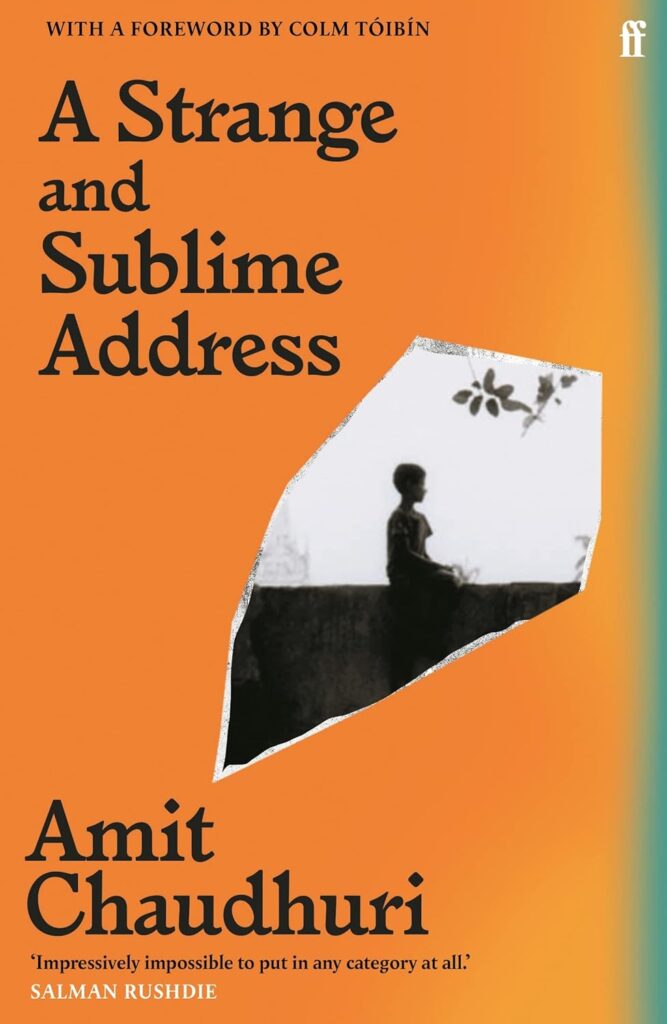

Which brings me to the book I returned to this week: A Strange and Sublime Address by Amit Chaudhuri. A short, achingly beautiful masterclass in stopping time.

Set in 1980s Calcutta, it’s a mesmerising time-capsule of a world where, at first glance, nothing much seems to happen. A ten-year-old boy visits his uncle’s house in Calcutta, spends the summer holidays watching his relatives. There are long, lazy afternoons beseiged by heatwaves, liberated by thunderstorms. There are trips to the market in an unreliable old car. There’s a ceiling fan that swings side to side, ‘like a great bird trying to fly’.

There’s one passage in particular that has lived in my head for years:

Each day there would be a power cut, and each day there would be the unexpected, irrational thrill when the lights returned. […] With what appeared to be an instinct for timing, the rows of fluorescent lamps glittered to life simultaneously. The effect was the opposite of blowing out candles on a birthday cake: it was as if someone had blown on a set of unlit candles, and the magic exhalation had brought a flame to every wick at once.

Growing up in India, I lived through my share of power cuts (and yours, too, I reckon). While I don’t remember them with much fondness, I certainly recognise the feeling Chaudhuri captures here — the ‘irrational thrill’ that shoots through you like a bolt of lightning when the world, dark for so long, lights up again.

Re-reading the passage now, it occured to me that its real beauty lies in what it leaves unsaid. That first comma in the first sentence — the pause between the electricity leaving and returning — is a power cut in prose form, shrouding in darkness the true source of its ultimate wonder. It’s that long suspension — fanning yourself with a folded-up newspaper, watching the candlelit shadows shiver across the walls, trying and failing, over and over again, to distract yourself from the fear that the lights may never light up again — that makes the climax so magical. It’s the wait that makes it worthwhile.

Such is the effect of Chaudhuri’s prose — the mastery with which he channels that most potent force of nostalgia — that, depsite my own harrowing memories of power cuts, I was left pining for one. Not because I miss the suffocating heat of the Indian summer. Because it feels like the only way to stop the relentless onslaught of cognitive overload. To pause.

Perhaps it would do us some good to try it, every once in a while — without suffering a power cut. (And without condemning outselves to some horrifying digital detox retreat.)

What if we tried to build it into our routines, I wonder. Deliberately missing that bus or train to take the next one, for instance. Or, like my father, arriving five hours early for a flight. What if we resisted the dopamine shots served by the algorithms and just sat around and waited?

If you do try it, this book might turn out to be the perfect companion.

FEATURED BOOK

A Strange and Sublime Address

by Amit Chaudhuri

Get it on Amazon, or from an independent bookshop (UK/US)