This summer, I treated myself to a rare gift — a somewhat expensive pair of trousers. (Olive green Stan Ray Fat Pants, if you must know.) Within a week, a pocket snagged on the sharp edge of a park bench and ripped. I was devastated, cursing the universe for conspiring against me, chiding myself for spending a hundred Great British Pounds on a pair of trousers.

Until my adult-er half told me to calm down and take them to the tailor around the corner. It made me laugh. What was this, 1925? Shall I stop by the cobbler, I asked. Drop in at the apothecary, too?

As it turned out, the drycleaners down the street had an in-house tailor. A kindly Bangladeshi man who took one look at my ripped pocket and nodded in that special South Asian way, dismissive yet reassuring. I went back the next day and the rip was gone. Not covered up, not stitched over — disappeared. All for under ten pounds.

At first, I was aghast that this simple solution hadn’t even occurred to me. Then, I was astounded by the world we live in that made this ignorance possible. You don’t forget about the existence of certain repairers, after all — dentists, auto mechanics, plumbers. How is it, then, that a tailor — not to mention the cobbler — sounds like a dated joke?

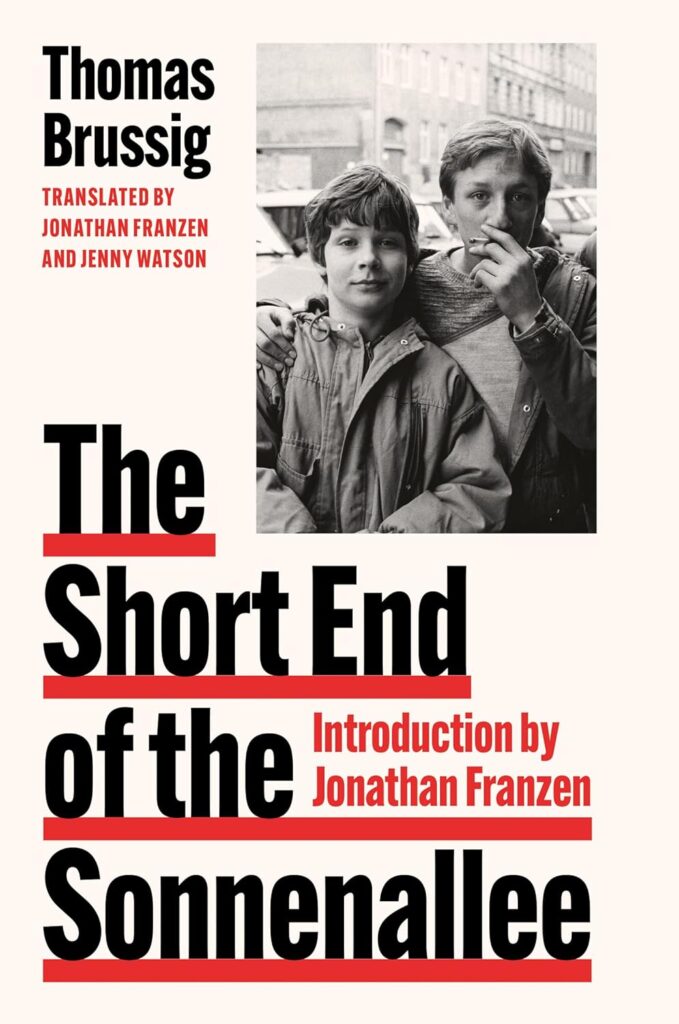

It made me return to a book I had bought a couple of years ago but had never got around to reading.

Worn: A People’s History of Clothing by Sofi Thanhauser turned out to be, like my neighbourhood tailor, an eye-opener. It may just make you look at your wardrobe in a whole new light.

The history of clothing is, of course, the history of our species — the only one mad enough to bedeck ourselves in fake fur. To create a focused, engaging story out of this vast, erm, canvas, the book is split into 5 sections — Linen, Cotton, Silk, Synthetics and Wool. Each one unpacks the history of the respective fabric — how it came to be, how it’s made these days and, most importantly, who makes it.

The book shows how cloth-making was, for thousands of years, both a primary vocation and a means of self expression for people across cultures. And it makes you think of the consequences of having lost both of those things in the span of a few decades.

Early on, the book casually drops a fact that made me pause for a long moment: for the first time in all of human history, buying clothes is cheaper than making them yourself.

And then, it goes on:

The contemporary clothing trade may be valuable, but the clothes produced are not. Between 2000 and 2014, clothing production around the world doubled. This was possible because clothing had become entirely disposable.

Fast fashion overtook our world so swiftly, so completely, that it’s not only cheaper to buy clothes than make them — that has been true for decades. It’s now cheaper to buy new clothes than repair them. With the likes of Shein, the cost of replacing something as trivial as a button or a zipper can be more than the cost of the garment itself.

This is absurd. Surely, we can all see that?

But the toll this transformation has taken on the environment, on our societies and traditions — on human lives — is often devastating. This is where Thanhauser’s book shines, turning the spotlight onto the people who have historically made our clothes and the ones who do it now, and how their lives have been transformed — rarely for the better.

In one memorable chapter, Thanhauser travels to the Yangtze Delta, the region in China famed for its millenia-old silk industry. It was here that the legendary Silk Road began and ended. It was where the tradition of silk weaving first flourished, turning ‘the shit of the silkworms’ — as one tour guide explains to Thanhauser — into garments that were one the most valuable objects in the world, the only gifts fit for emperors who had it all. Such glorious objects are now confined to museums, glowing behind glass panes like alien artefacts. And the land that made them is now a megapolis, its mulberry fields replaced by a concrete forest. When Thanhauser asks one of the last remaining silk farmers in the region about it, he says, simply: ‘My heart is dying.’

It is indeed heartbreaking to realise what we have lost. Not only objects of immese beauty, but the art of creating them. For all of our history, making clothes was one of the most accessible forms of art, a means of self expression available to most, admired by all. Today, while a few successful designers are celebrated for their vision, the act of creation itself has been devalued into nothing. The people who may once have crafted wonders now sit crammed into ghastly sweatshops. This loss of everyday creativity, I think, has made us all poorer, leaving a spiritual hole in our psyches.

I don’t imagine most of us will ever learn how to make our own clothes. In fact, it’s possible that later generations wouldn’t even think of clothes as something that can be made by hand. But, for now, there are still people keeping the art alive. Perhaps it’s worthwhile to find them, to support them, to get our clothes made and repaired by them. And to buy clothes worth repairing in the first place.

FEATURED BOOK

Worn: A People’s History of Clothing

by Sofi Thanhauser

Get it on Amazon, or from an independent bookshop (UK/US)